The Brazilian Association of Sanitary and Environmental Engineering (ABES) is a non-governmental organization founded in 1966, with the purpose of developing and improving activities related to sanitary engineering and environment, stimulating social consciousness and actions that could meet conservation demands as well as environmental and life quality improvement within the Brazilian society.

The Brazilian Association of Sanitary and Environmental Engineering (ABES) is a non-governmental organization founded in 1966, with the purpose of developing and improving activities related to sanitary engineering and environment, stimulating social consciousness and actions that could meet conservation demands as well as environmental and life quality improvement within the Brazilian society.

In its 47 years of existence, ABES has always been present, participating actively in crucial political moments for the environmental sanitation sector. Its historical trajectory has been characterized by decisive political and professional positioning. The association holds a prominent position as a technical reference within the Brazilian environmental sanitation sector. Besides international prestige, the association holds a deserving institutional respect achieved throughout its existence. ABES has projected itself into dealing with subjects concerning social and economic development, most precisely when linked to public sanitation policies. Its prompt interventions have always been made at relevant moments and always dealing with facts that instigated its professional consciousness and ethical sense.

The current sanitation position is a result of the continuous evolution that follows people on Earth. Step by step, mankind has been accumulating observations, experiences, learning, knowledge, skills and science.

Sanitation is like a safe conducting wire for the comprehension of mankind evolution, from civilization to civilization. Among Egyptians, water was considered a key element and it could be found in the Nile River which was thought to be a riches generator and the object of environmental disasters. Ever since then, known as a source of life, water was also considered to be life threatening. Egyptians disposed of designers that were able to build transportations and irrigation canals. At the time of Christ, the people from Nazca, antecedents of the Incas in the south of Peru, were able to dig tunnels on hillsides to capture defrosting water as well as groundwater for irrigation and other purposes. Just as the Romans, the Incas were skilled aqueduct constructors.

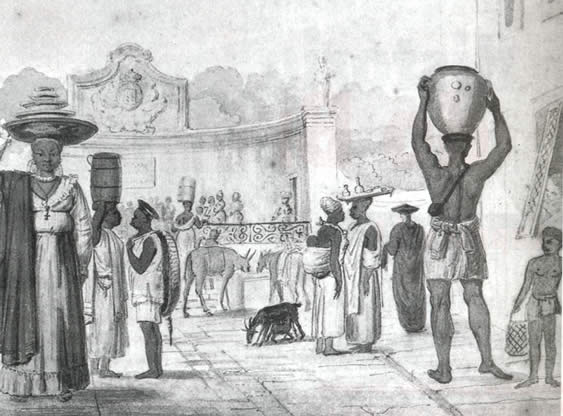

Centuries later, during colonial Brazil, home hygiene was a luxury that even the privileged couldn´t have access to. A reminder of this discrimination era can still be seen in São Luíz, the capital of Maranhão, where “Beco da Bosta”, meaning the “crap alley”, is the original name of an alley through which slaves had access to the sea and to which they would carry travel bags containing human waste that came from their lords´ home. In Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the Empire, the situation was not less degrading. There, sanitation loads were carried through the night inside wooden casks or clay vessels. Slaves selected to perform this task were known as “tigres”, meaning tigers. Someone with a capitalist spirit saw a good business opportunity out of that. The transportation started then to be made by donkey drawn carts that would take the loads to their final destinations which were as far as possible from the elites. Entrepreneurs would charge a fixed rate for home collecting, transportation and final destination. There is the embryo of the business management of sanitation sewerage services. This culture that endured for more than 300 years, to some extent, still endures: “I take the problem away from home; in the future it´s every man for himself”. This reality, either in a lower or higher level of gravity is evidenced by the occurrence of valas negras, meaning black ditches, in the outskirts of almost every city and rural areas in Brazil.

During the Empire, Rio de Janeiro was given the first wastewater network. Many were the foreign travelers that criticized the promiscuous sanitation conditions in which the people and even the Imperial Court were living in. Reports referred to the city as a colorful, happy and stinky city. And then did the Emperor Dom Pedro II order the project of a sanitation sewerage and drainage system following the best technology that was being implemented in England. The concession of the services was given to João Frederico Russell who organized in London a company named The Rio de Janeiro City Improvements, with an 835 thousand pounds capital. City´s contract endured for 90 years, from 1857 to 1947.

During the first years of Republic, the Brazilian capital of that time suffered from fulminant yellow fever and smallpox epidemics. Thousands of people would die for the insalubrious environment. It was then that Oswaldo Cruz managed to implement obligatory vaccination. In 1904, the Vaccine Uprising was not only stemmed by the press intolerance and the people´s ignorance but also by the low level of medical science taught in schools by then. Doctors didn´t study microbiology satisfactorily. Also, they did not know the causes and vectors of those epidemic diseases. In this matter, the work of Saturnino de Brito, a sanitary engineer, deserves to be highlighted as he conducted some of the most important studies on basic sanitation and urban planning, taking many locations in the country away from epidemics and insalubrity. Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Saturnino de Brito worked directly in 53 Brazilian cities among which were Santos, Rio de Janeiro and Vitória.

A new demographic design begins to be configured in 1950, with the conversion of a rural Brazil (agriculture and stock breeding riches) to an urban Brazil (industrial riches). The consequences of population spatial redistribution – in verified number and speed – were not foreseen during the planning of public policies. Omission and lack of urban development-oriented investments led both, cities physical infrastructure and social equipments to deteriorate in a way in which they were compromising the population´s quality of life. In the late 1960s, according to a research conducted by Acqua-Plan for the Programa de Modernização do Setor de Saneamento (PMSS), meaning the Sanitation Sector Modernization Program, the attendance indices of people who had water and wastewater services were of 45% and 20% repectively.

In an attempt to face that alarming situation the Federal Government created, in 1968, regulated by Decree-Law 949/1969, the Sanitation Financial System (SFS) under the responsibility of the Housing National Bank (BNH), followed, in 1971, by the institution of the Sanitation National Plan (PLANASA).

The vexatious sanitation situation in Brazil hurt the few dedicated sanitarists´ pride. At first, the hurt ones were the doctors. It was a time in which every doctor was trying to fight the immediate effects of diseases. The children were already able to be treated with more effective prescribed medicines but they would continue to die frequently if they couldn´t have the opportunity to live in an adequate sanitary environment. It was the right time to fight the causes. It was time for the engineers to act.

The first studies, plans and projects for the construction of a much needed sanitary infrastructure in Brazil, were being conducted inside engineering schools. In 1954, at the Public Health School in São Paulo, the first seminar led by teachers of Sanitation, Sanitation Engineering and Correlative Subjects was taking place. Two other sanitarist meetings were held in 1956 and 1958. The initiative continues even today, incorporated to the Congresses of ABES.

Reports from pioneers tell about the existence of a high level of professional agitation among sanitary engineers in the early 1960s. Sanitary engineering had already become relevant technically and institutionally, both by its size and good results in works performed everywhere in the country or by definitely conquering a spot within the planning of public policies in basic sanitation, health and environment. Conditions for the accomplishment of a dream to institute an entity in the sanitation sector were favorable: Brazil was growing, modernizing and increasingly demanding major and minor sanitary engineering works.

Brazilian respected and noticeable technical development of sanitary engineering was due to the continental knowledge interchange. In 1942 the 11th Panamerican Sanitary Conference took place in Rio de Janeiro and the creation of a Permanent Sanitary Engineering Commission was recommended. Two Interamerican Engineering conferences were held in 1946 being the first one in Rio de Janeiro and the second one in Caracas. As suggested in the first conference and endorsed in the second, the Interamerican Sanitary Engineering Association (AIDIS) was created. In 1948 the first Rio de Janeiro Section General Assembly takes place. Step by step, new subsections of AIDIS were being implemented in Brazil.

Counting on a wealth of sanitary engineering knowledge resources, many monumental works were carried out throughout the 1960s in Rio de Janeiro: the construction of Aterro do Flamengo, together with its artificial beach, the enlargement of 120 meters on Av. Atlântica, the construction of the oceanic interceptor system as well as the submarine effluent outlet and the implementation of the Guandu system with its 42 kilometers of tunnels and only one lifting. It was needed some help from the Portuguese to build the oceanic interceptor system because there wasn´t any project experience since there wasn´t any similar project that had been built in Brazil. The Civil Engineering National Laboratory of Lisbon (LNEC) was in charge of developing the hydraulic model, with the study of sea currents, tidal movement, wave strength and other variables.

Because of its stimulating environment, there were many sanitation international authorities that came to Brazil to give lectures, report studies and provide technical support. Among them are Abel Wolman, Emeritus Professor at John Hopkins University, Francis Montanari and Glenn Wagner.

The greatest innovator and performer of sanitation works in Rio de Janeiro was the engineer Enaldo Cravo Peixoto, State Secretary of Works and first president of ABES together with the engineer José Roberto A.P.  do Rego Monteiro, who has also been ABES president and director of the Housing National Bank (BNH). Many of the technical premises from BNH come from these two former presidents. In 1962, during Carlos Lacerda´s administration, Enaldo signed a loan of US$ 80 million from BID to implement the Guandu System. The value itself wasn´t considered to be unusual but the extended period conceded for its amortization. Sanitation works should be long-term bounded, thought Enaldo, in a way that charges and benefits would be extended to the next generations.

do Rego Monteiro, who has also been ABES president and director of the Housing National Bank (BNH). Many of the technical premises from BNH come from these two former presidents. In 1962, during Carlos Lacerda´s administration, Enaldo signed a loan of US$ 80 million from BID to implement the Guandu System. The value itself wasn´t considered to be unusual but the extended period conceded for its amortization. Sanitation works should be long-term bounded, thought Enaldo, in a way that charges and benefits would be extended to the next generations.

The political and financial model that would be the base for the creation of BNH in the next decade was set out. By the way, BNH´s main purpose was focused on housing. Sanitation came from the conviction that one thing couldn´t do without the other as said by the engineer Rego Monteiro. It was his obsession to qualify the sanitation sector with well prepared technical personnel. In BNH, he conquered space to put this attempt into practice, having ABES as his main partner in many projects of personnel qualification.